On May 23, 1939, a shipload of 925 Jews, including families with small children, some of them toddlers, left the port of Hamburg for Cuba. They were grateful to be escaping Nazi discrimination. Though every one of them carried a visa for Cuba, none were admitted. The ship, the St. Louis, then turned its prow toward America, hoping to find a safe harbor there. Instead, they found that door closed as well. Michael Barak, one of the small children aboard the ship, described the U.S. “welcome” at a 2002 reunion of those passengers in Jerusalem:

When approaching Miami of the “free” country, President Roosevelt sent the U.S. navy to prevent any entry. On top of that, he warned any country in the region from letting any of the “damned” Jews to land safely on their soil. In Canada, the head of immigration said, after being asked how many Jews of that ship could be accepted, “None is too many.”

The ship sailed along the coast of Florida for five days, as its captain did what he could to find an open door somewhere in the world. In all, three weeks were spent trying to find refuge. Urgent cables were sent to every level of the U.S. government, including two personal appeals to President Roosevelt. No reply was forthcoming. Instead, Coast Guard boats patrolled to prevent anyone from swimming to shore. On June 7, the St. Louis was forced to set sail back across the Atlantic, where it was able to disembark its precious cargo between England, Holland, France, and finally Belgium. Of the passengers aboard the St. Louis, most of the families were separated when the Nazis took control of Holland, Belgium, and France the following year (1940). About 260 were deported immediately to killing centers, and nearly half of them died in the Holocaust.

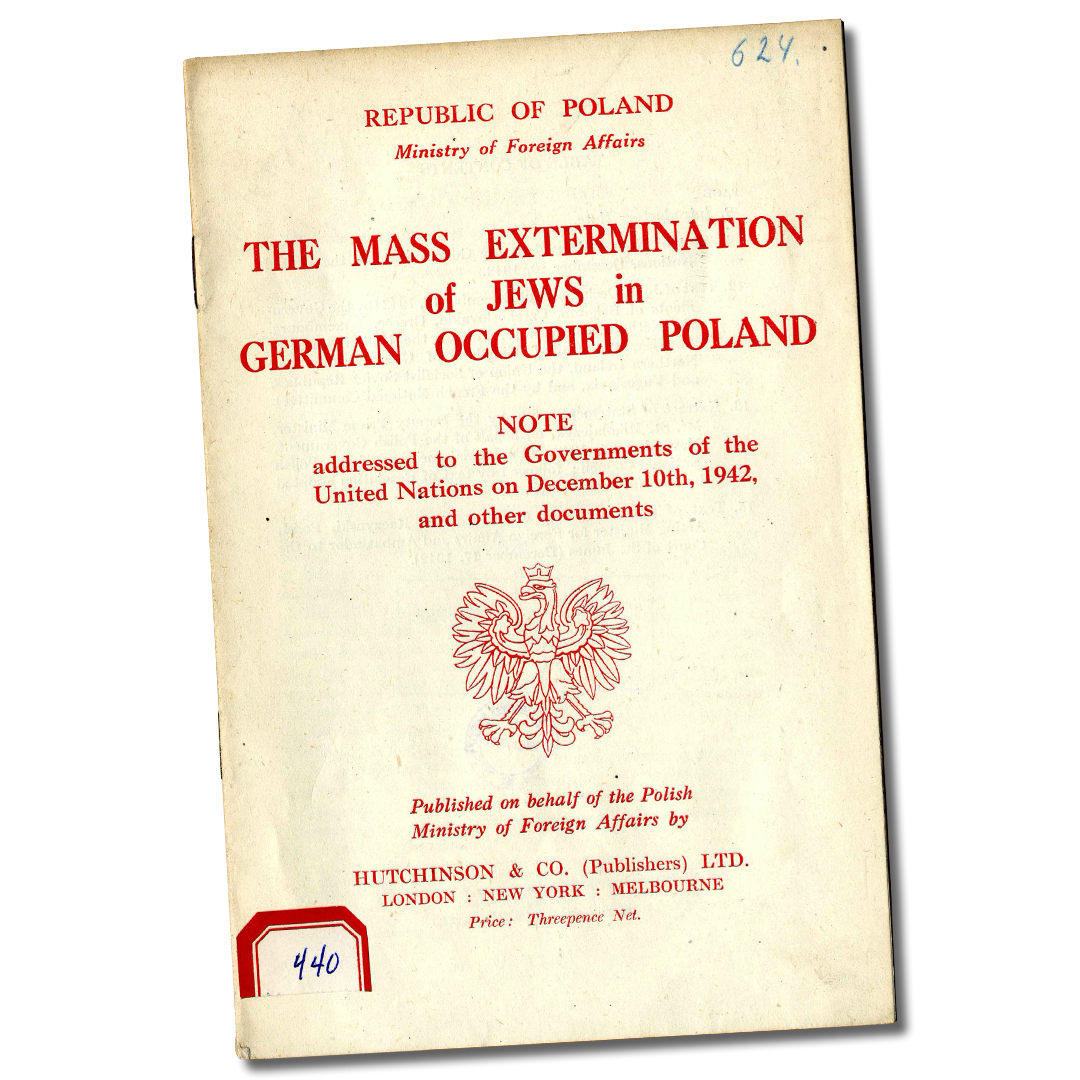

The president’s inaction regarding the St. Louis caused a change of heart among some of his supporters, who felt that Roosevelt bore some responsibility for the devastating tragedy. It would be a visit from a Polish diplomat, Jan Karski, that would provide even more evidence of the chief executive’s lack of sympathy for the plight of European Jews. Karski was dispatched to London and to Washington to deliver a firsthand account of the atrocities being visited on the Jewish people. He met first with Justice Felix Frankfurter who, though not convinced, took Karski to the White House to meet with Roosevelt. Karski reported to the president:

There is no exaggeration in the accounts of the plight of the Jews. Our underground authorities are absolutely sure that the Germans are out to exterminate the entire Jewish population of Europe. Reliable reports from our own informers give us the figure of 1,800,000 Jews already murdered in Poland up to the day when I left the country.

Karski later gave a firsthand report of the president’s response to his plea: “You will tell your leaders that we shall win this war. You will tell them that the guilty ones will be punished for their crimes. You will tell them that Poland has a friend in this house.” Roosevelt then changed the subject and moved on to the next topic for discussion. His wife, Eleanor, said this about the way her husband dealt with unpleasant things: “If something was unpleasant and he didn’t want to know about it, he just ignored it. He always thought that if you ignored a thing long enough, it would settle itself.”

In an article for Yahoo! Voices, Brandon Moran summarized Paper Walls, a book by author David Wyman. Brandon wrote: “The ‘Paper Wall’ around Central Europe in the summer and fall of 1940 slowed the migration of Germans into the U.S. dramatically. This wall consisted of stringent legislation and policy passed during this period, tightening the strangle hold on immigration into the U.S. Avra Warren played a large role in doing so. Warren worked to raise legislation for stricter immigration controls. His goal was to protect the country from subversive aliens. The new legislation suspended temporary immigration because temporary immigrants could have subversive connections or intentions. Warren and Assistant Secretary of State, Breckinridge Long, devised a modus operandi that effectively walled out any applicants the State Department wished to exclude.”

Citing Long, Wyman provides an issued memorandum spelling out his intent:

We can delay and effectively stop for a temporary period of indefinite length the number of immigrants into the United States. We could do this by simply advising our consuls to put every obstacle in the way and to require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative advices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of the visas. However, this could only be temporary.

Consular officers were instructed to decline visas to applicants who had “parents, children, husband, wife, brothers, or sisters in residence in territory under the control of Germany, Italy, or Russia. Many bills and laws were introduced at this time, adding cement to the Paper Wall. The flow of immigrants into the U.S. had slowed to a trickle. By July 10, the U.S. government ordered all German consulates closed.… By late 1941, the doors into the U.S. had been all but closed.

Show Your Support By Giving Now